|

T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

THE BIBLE AND GOD -

THE FOUNDATIONS OF BELIEF AND UNDERSTANDING

From 'GOD a Brief History -The Human Search for Eternal Truth',

John Bowker pp176 and 177

The beginning of the Jewish story of God is bound up with the beginning of the Jewish people. “A wandering Aramean was my ancestor” (Deuteronomy 26.5), say the Jewish people, each time they bring the offering of the first fruits to God. How a group of nomadic herdsmen came to believe that God had called them to specific work and responsibilities in the world is the story told in the Bible.

The Bible story in briefest form is this: God is the One who has created all things. The Bible begins “in the beginning God created..." (Genesis 1.1). Genesis goes on to show how the goodness of all creation is disturbed by humans deciding to pursue knowledge and make their own decisions.

The opening chapters of Genesis portray the progressive break-up of relationships – between husband and wife, humans and God, humans and the natural order, town and country, the God fearing and those who are not, and between ;different nations, culminating in the confusion of languages after the building of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11.1-9).

The Bible as a whole then shows how God begins the work of repair, bringing healing and renewal. This process is focused in a series of agreements known as covenants, made at first with individuals, such as Noah and Abraham, through Moses, and then with the whole nation descended from Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Thus the people of Israel exist to be the instrument of God’s work of the repair in the world, and they do this not just for their own sake, but so that all people may learn to recognize who and what God is (see, e.g., Habakkuk 2.14, Zechariah 8.20-3).

God takes the initiative in calling Israelites to do this work and in helping them to do it. When they are in slavery in Egypt, God rescues them dramatically in the Exodus, leading them into the wilderness and onto the Promised Land of Canaan, whose people they are told to conquer. In the wilderness God gives them, through Moses, the laws in the Torah that become the basic conditions of the new and enduring covenant ('Torah' means “guidance”: it applies to the whole of the first five books of the Bible, and indeed to the whole of scripture, but it may also apply to the specific laws).

Fundamental to the covenant agreement is the recognition That God is truly God, the only one who is God, in contrast to the many claimed Gods in the world around. The most profound statement is found in Deuteronomy 6.4: "Hear (Hebrew Shema, hence the name Shema given to the basic Jewish statement of faith that begins with this verse "O Israel, the Lord your God the Lord is One.”

The people however by no means always keep to the terms of the covenant agreement. They continue often, to invest their gifts, sacrifices and allegiance in the local gods. Even when it seems necessary because of threats from neighboring countries and invading Philistines, to draw the people together under a single leader as king, this is seen as a failure of trust in the sovereignty of God. But God endorses David as their King and, after David captures Jerusalem makes a new covenant with him and his descendants as meshiach (messiah or anointed ed one”). Solomon, David’s son builds the Temple, but after his death, the kingdom is split and the period of kings proves to be another failure.

In protest against the many betrayals of God, prophets emerge speaking directly in the name of God and challenging the people with the words, “Thus says the Lord…”. The prophets are not opposed to the covenant and its laws although they seldom mention them directly, they are urging the people to live in the way that God demands. Their appeals are in vain and God summons first the Assyrians in the 8th century BCE to destroy the northern kingdom, and then the Babylonians in the 6th century BCE to destroy Jerusalem and the Temple and take take the people into Exile. After the exile the Temple is rebuilt, and the priests become dominant in deciding matters of faith and practice: since God has given Torah to Israel, its teachings must be followed if the people are to prosper. It becomes vital therefore to show what Torah means in daily life.

After the Biblical period it seems for a while that they are prospering under God. During the rule of a family known as the Hasmonaeans (142-63B CE) the people live in an independent state, and even though their independence is removed by the Romans, the Herods reinforce the prosperity of Jerusalem. Two further attempts at independence from Rome end in disaster in the years 70 and 135 CE, the rebellions are defeated, and the Temple is once more destroyed and is portrayed in vivid and dramatic terms.

Throughout this story God is portrayed in vivid and dramatic terms. But all this is a simplified picture from a faith community trying to understand itself, its dealings with God and the nature of the One with whom they are involved. The Bible is an anthology of writings from more than 1,000 years. It reveals not only that simple picture, but also a process of change and corection, of truth leading to transformation, in the understanding of the name and nature of God. The Jewish understanding of God is deeply embedded in history: that history is by no means easy to recover, but it, too, belongs to the Jewish story of God.

HEBREW BIBLE,

(also called

HEBREW SCRIPTURES, OLD TESTAMENT or TANAKH)

Encyclopaedia Brittanica: Hebrew Bible

The collection of writings that was first compiled and preserved as the sacred books of the Jewish people. It constitutes a large portion of the Christian Bible. For full treatment, see biblical literature.

In its general framework, the Hebrew Bible is the account of God’s dealing with the Jews as his chosen people, who collectively called themselves Israel. After an account of the world’s creation by God and the emergence of human civilization,

the first six books narrate not only the history but the genealogy of the people of Israel to the conquest and settlement of the Promised Land under the terms of God’s covenant with Abraham, whom God promised to make the progenitor of a great nation. This covenant was subsequently renewed by Abraham’s son Isaac and grandson Jacob (whose byname Israel became the collective name of his descendants and whose sons, according to legend, fathered the 13 Israelite tribes) and centuries later by Moses (from the Israelite tribe of Levi).

The following seven books continue their story in the Promised Land, describing the people’s constant apostasy and breaking of the covenant; the establishment and development of the monarchy in order to counter this; and the warnings by the prophets both of impending divine punishment and exile and of Israel’s need to repent.

The last 11 books contain poetry, theology, and some additional history.

The Hebrew Bible’s profoundly monotheistic interpretation of human life and the universe as creations of God provides the basic structure of ideas that gave rise not only to Judaism and Christianity but also to Islam, which emerged from Jewish and Christian tradition and which views Abraham as a patriarch (see also Judaism: The ancient Middle Eastern setting). Except for a few passages in Aramaic, appearing mainly in the apocalyptic Book of Daniel, these scriptures were written originally in Hebrew during the period from 1200 to 100 BCE. The Hebrew Bible probably reached its current form about the 2nd century CE

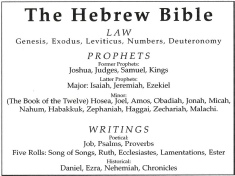

The Hebrew canon contains 24 books, one for each of the scrolls on which these works were written in ancient times. The Hebrew Bible is organized into three main sections: the Torah, or “Teaching,” also called the Pentateuch or the “Five Books of Moses”; the Neviʾim, or Prophets; and the Ketuvim, or Writings. It is often referred to as the Tanakh, a word combining the first letter from the names of each of the three main divisions. Each of the three main groupings of texts is further subdivided. The Torah contains narratives combined with rules and instructions in Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. The books of the Neviʾim are categorized among either the Former Prophets—which contain anecdotes about major Hebrew persons and include Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings—or the Latter Prophets—which exhort Israel to return to God and are named (because they are either attributed to or contain stories about them) for Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and (together in one book known as “The Book of the Twelve”) the 12 Minor Prophets (Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi). The last of the three divisions, the Ketuvim, contains poetry (devotional and erotic), theology, and drama in Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Song of Songs (attributed to King Solomon), Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles.

Many Christians refer to the Hebrew Bible as the Old Testament, the prophecy foretelling the advent of Jesus Christ as God’s appointed Messiah. The name Old Testament was devised by a Christian, Melito of Sardis, about 170 ce to distinguish this part of the Bible from the New Testament, which recounts the ministry and gospel of Jesus and presents the history of the early Christian church. The Hebrew Bible as adopted by Christianity features more than 24 books for several reasons. First, Christians divided some of the original Hebrew texts into two or more parts: Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles into two parts each; Ezra-Nehemiah into two separate books; and the Minor Prophets into 12 separate books. Further, the Bibles used in the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and some Protestant churches were derived initially from the Septuagint, the Greek-language translation of the Hebrew Bible produced in the 3rd and 2nd centuries bce. This included some books deemed noncanonical by Orthodox Judaism and most Protestant churches (see also Apocrypha), slightly longer versions of Daniel and Esther, and one additional psalm. Moreover, the Ethiopian Tewahdo Orthodox Church, one of the Oriental Orthodox churches, also includes within its Old Testament two works considered by other Christian churches to be pseudepigraphical (both noncanonical and dubiously attributed to a biblical figure): the apocalyptic First Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees.

(For a list and links to each book go to BibliaHebraica)

TORAH

EncyclopAedia Brittanica: Torah

Torah in Judaism, in the broadest sense the substance of divine revelation to Israel, the Jewish people: God’s revealed teaching or guidance for mankind. The meaning of “Torah” is often restricted to signify the first five books of the Old Testament, also called the Law or the Pentateuch. These are the books traditionally ascribed to Moses, the recipient of the original revelation from God on Mount Sinai. Jewish, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant canons all agree on their order: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

The written Torah, in the restricted sense of the Pentateuch, is preserved in all Jewish synagogues on handwritten parchment scrolls that reside inside the ark of the Law. They are removed and returned to their place with special reverence. Readings from the Torah (Pentateuch) form an important part of Jewish liturgical services.

The term Torah is also used to designate the entire Hebrew Bible. Since for some Jews the laws and customs passed down through oral traditions are part and parcel of God’s revelation to Moses and constitute the “oral Torah,” Torah is also understood to include both the Oral Law and the Written Law.

Rabbinic commentaries on and interpretations of both Oral and Written Law have been viewed by some as extensions of sacred oral tradition, thus broadening still further the meaning of Torah to designate the entire body of Jewish laws, customs, and ceremonies.

The books that are found in the Bible were selected on account of their divine inspiration. These texts have become a governing guide for the Jewish people. Nevertheless, there are numerous other texts that never made it into the Bible, many of which are lost today. This choosing of texts for the Bible is referred to as canonization, a method of measuring a text’s importance. Canonization is the long procedure of collecting and sequencing of the texts in an order of authority and importance.

CANONIZATION

Jewish Virtual Library

The books that are found in the Bible were selected on account of their divine inspiration. These texts have become a governing guide for the Jewish people. Nevertheless, there are numerous other texts that never made it into the Bible, many of which are lost today. This choosing of texts for the Bible is referred to as canonization, a method of measuring a text’s importance. Canonization is the long procedure of collecting and sequencing of the texts in an order of authority and importance

The Pentateuch (Torah), as we know it today, was completed during the Babylonian exile, by the time of Ezra. The Neviim (Prophets) were finalized during the Persian era, approximately 323 BCE The conclusion of the last section of the Bible, ketuvim (Writings) is debated; however, a majority of scholars believe its final canonization occurred in the second century CE

The canon of the Hebrew Bible is somewhat different than that of the Greek Bible (which is the basis for the Christian Bible). The Greek Bible includes several additional books, which were not accepted into the Hebrew Bible. These texts include – 1-4 Maccabees, Judith, and Psalms of Solomon. Furthermore, the two Bibles differ in their sequence of the texts and writings, as well as the order of importance in the placement of texts.

WHAT IS THE TORAH?

About Religion

The Torah is Judaism’s most important text. It is composed of the Five Books of Moses and also contains the 613 commandments (mitzvot) and the Ten Commandments. The word “Torah” means “to teach.”

Traditionally a Torah is written on a scroll that is then wound around two wooden poles. This is called a “Sefer Torah” and it is handwritten by a sofer (scribe) who must copy the text perfectly. When in modern printed form, the Torah is usually called a “Chumash,” which comes from the Hebrew word for the number “five.”

The writings of the Torah are also part of the Tanach (Hebrew Bible), which contains not only the Five Books of Moses (Torah) but 39 other important Jewish texts. The word “Tanach” is actually an acronym: “T” is for Torah, “N” is for Nevi’iim (Prophets) and “Ch” is for Ketuvim (Writings).

THE FIVE BOOKS OF MOSES

The Five Books of Moses begin with the Creation of the World and end with the death of Moses. They are listed below according to their English and Hebrew names. In Hebrew, the name of each book is derived from the first unique word that appears in that book.

Genesis (Bereisheet) – “Bereisheet” means “in the beginning.” This book talks about the Creation of the World, the Great Flood, and also tells the stories of Judaism’s patriarchs and matriarchs. These stories begin with Abraham and Sarah and end with Joseph in Egypt.

Exodus (Shemot) – “Shemot” means “names” in Hebrew. This book tells story of the Israelites bondage in Egypt, their journey to Mt. Sinai (where the Ten Commandments are received) and their wanderings in the wilderness.

Leviticus (Vayikra) – “Vayikra” means “And He Called” in Hebrew. This book deals mostly with priestly matters such as rituals, sacrifice, atonement and ritual purity.

Numbers (BaMidbar) – “BaMidbar” means “In the wilderness” in Hebrew. This book talks about the Israelites wanderings in the desert as they continue towards the Promised Land.

Deuteronomy (D’varim) – “D’varim” means “words” in Hebrew. This is the final book of the Torah. It recounts the Israelites’ journey according to Moses and ends with his death just before they enter the Promised Land.

OVERVIEW - TORAH

Ancient History Encyclopedia by Justin King

The Torah, also known as the Pentateuch (from the Greek for “five books”), is the first collection of texts in the Hebrew Bible. It deals with the origins of not only the Israelites, but also the entire world. Though traditionally the Hebrew word torah has been translated into English as “law” because of its translation in the Septuagint (the Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible) as “nomos (law)”, it is better understood and translated as “teaching” or “instruction.” The Torah is the result of a long process of editing (or redaction, as it is called by scholars). This means that there is no one date that one can be pointed to as the date of composition. Most scholars think that the final major redactions took place after 539 BCE, when Cyrus the Great conquered the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The Torah was, and continues to be, the central set of sacred texts (scriptures) for Judaism because of its focus on the proper ways (ritually, ethically, theologically, etc.) for the tribes of Israel to live, though how exactly one is to live out the Torah was, and continues to be, a complicated issue.

The Torah is composed of five books which present us with a complete narrative, from creation to the death of Moses on the banks of the Jordan River. The question of the relationship between history and the narratives of the Torah is complex. While the Torah mentions historical places (e.g. Ur in Genesis 11) and historical figures (e.g. Pharaoh in Exodus 1, perhaps Ramses II), we have no archaeological or other textual record of the specific events or the key players (e.g. Moses) described.

THE TORAH IS COMPRISED OF FIVE BOOKS WHICH PRESENT US WITH A COMPLETE NARRATIVE, FROM CREATION TO THE DEATH OF MOSES ON THE BANKS OF THE JORDAN RIVER.

Genesis is broken up into four literary movements. The first movement is known as the “primeval history,” which tells the story of the world from “creation” up to the call of Abraham. The second movement is the Abraham cycle, chapters 12.1-25.18, which tells the story of Abraham from his call to his death. The third movement, chapters 25.19-36.43, is the Jacob cycle which tells the story of Jacob from his birth up to the dreams of his son Joseph. The fourth movement, chapters 37-50, is the Joseph cycle which tells the story of Joseph and his brothers. The narrative of Genesis begins with the creation of the world, but with each movement the narrative becomes more focused. It moves from focusing on the entire created order, to humanity, to focusing on a specific family (that of Abraham), to focusing one of Abaraham’s sons (Jacob/Israel), and culminating in the “creation” of the tribe of Israel and the presence of Israelites in Egypt.

Exodus can be broken up into three general sections: the liberation from Egypt (chapters 1.1-15.21), the giving of the Law to Moses on Sinai (15.22-31.18), and the start of the 40 year (one generation) desert wandering (32-40).

Leviticus In contrast to the rest of the Torah, Leviticus contains very little narrative material, but is dependent upon the narrative of Exodus. The material of the P source (see below) in Exodus primarily describes the construction of the cultic implements (e.g. the Ark of the Covenant). In Leviticus the focus is on the enactment of the cult, particularly the role of the Levites, which is to teach the distinction “between the holy and the common, and between the clean and unclean” (Lev 1.10; 15.31, NRSV).

Numbers There are two ways to understand the structure of Numbers. First, one can view its structure as geographic, with each section corresponding to a particular location in the desert wandering: Wilderness of Sinai (1.1-10.10), the land east of the Jordan River, also known as "Transjordan" (10.11-22.1), and the land of Moab (22.2-36.13). However there are two key events which can also be used to understand the structure of the book, the two military censuses of chapters 1 and 26.

Deuteronomy Deuteronomy gets its English name from the Greek word deuteronomion (second law), which is a poor translation of the Hebrew phrase mishneh hattorah hazzot (a copy of this law) in Deuteronomy 17.18. It is also the only book of the Torah to make specific claims for Mosaic authorship.

Four editorial superscriptions make the structure of Deuteronomy clear. Part 1 (1.1-4.43) is primarily Moses reflecting on the story of the Israelites from Sinai (or Horeb as it is called in Deuteronomy) to Transjordan and a discussion on the destiny of God’s people. Part 2 (4.44-28.68) is the key part of the book as it contains the giving of the Torah (the authoritative teaching and instruction) dictating how Israel is to live (ethically, cultically, politically, socially, etc.) if it wants to secure its political existence. Part 3 (29-32) contains a covenant Moses makes with Israel and relates the commissioning of Joshua. Part 4 (33-34) concludes with blessing of the tribes of Israel, and a narrative about the death and burial of Moses. Deuteronomy, and as such the Torah, concludes with the people of Israel poised to enter the promised land.

c. 1000 BCE Tentative date of the composition of the Torah's J source.

c. 900 BCE Tentative date of the composition of the Torah's E(?) source.

c. 621 BCE Tentative date of the composition of the Torah's D source.

c. 539 BCE - c. 330 BCE Tentative date of the redactional (=editorial) activity of the Torah's P source.

c. 250 BCE Torah is translated into Greek in Alexandria, Egypt.

Traditionally, it was largely assumed (by Jews and Christians alike) that Moses was the author of the Torah. However, in the 17th century CE, this assumption began to be challenged. In the 19th century CE, German scholar Julius Wellhausen put forth the first major formulation of what is known as the Documentary Hypothesis in his Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (first published in German in 1878 CE, and in English as Prolegomena to the History of Israel in 1885 CE). Since then, the Documentary Hypothesis has undergone significant revision and among many scholars, particularly those in North America, it remains the dominant theory for explaining the composition of the Torah.

Simply put, this theory states that the whole of the Torah is comprised of four main sources: J (Yahwist), E (Elohist), D (Deuteronomistic), and P (Priestly). It is most likely that these sources are not texts, but particular groups of individuals who were initially responsible for the composition and transmission of the sources (as oral traditions and/or written compositions) which were later incorporated into the Torah by the P source. Scholars use "source" in a very general way in this context to allow for the ambiguity of what these "sources" were.

The J source earns its name from the fact that it prefers the Tetragrammaton (“The four letters”), YWHW (usually pronounced as “yahweh,” though this pronunciation is debated), for the name of the god of Israel. The reason that it is the "J" source and not the "Y" source is that the theory was first put forth in Germany, where YHWH is spelled with a J rather than a "Y." YHWH is made to appear very human (e.g. YHWH is said to walk with humans [see Genesis 2]), the characters of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are not idealized in the narrative, and morality is not absolute. Further, it is the nation of Judah which is emphasized. This source is traditionally dated between 1000 BCE and 900 BCE, which possibly is contemporaneous with the courts of David and Solomon.

Like J, the E source gets its name from its preferred name for the god of Israel. It uses the generic Hebrew word elohim, which can mean “gods,” “god,” (as generic terms for other deities), or as “God” (referring specifically to the god of Israel). In contrast to J, E emphasizes the Northern Kingdom of Israel. Instead of directly speaking to humanity, the E source had God speaking directly to Abraham. This source is usually dated in the 8th or 9th centuries BCE and was likely an import from the Northern Kingdom of Israel. E and J were likely edited together at a point before the exilic period with J being the primary source with E edited in. Therefore, some scholars treat J and E as one source (calling it the JE source) or leave out E altogether.

D, or the Deuteronomist, is most likely a school of scribal reformers from around the time of Josiah, c. 621 BCE, a king of the Kingdom of Judah. D is responsible for the book of Deuteronomy and little else in the Torah. However, it is likely responsible (as authors and/or editors) for the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings (known as the Deutronomistic History) as well as editor of Jeremiah and sections of the Book of the Twelve (Hosea-Malachi). D is characterized by absolute morality, worship centered in the Jerusalem Temple, and the cycle of sin and repentance. It is possible that some form of what we know as Deuteronomy was found by Josiah’s High Priest as recorded in 2 Kings 22 and 2 Chronicles 34.

P, or the Priestly Source, is the most easily identified of the three sources responsible for Genesis – Numbers. This source is characterized by outlines, order, genealogy, and ritual and sacrifice. Like J, P focuses on Judah. Whereas JE is clearly narrative, P contains both narrative (such as the creation account in Genesis 1 and the flood narrative of Genesis 6—8) and ritual material (such as the Holiness Code of Leviticus 17—26). This makes it very difficult to characterize the genre of P. It is usually thought to be the last of the four sources to compose and redact the Torah, likely active sometime during the Persian period 539 - c. 330 BCE.

The Documentary Hypothesis is not without its problems. It has long been recognized that E lacks a clear narrative flow. If it was ever an independent source, it was long absorbed into J. For this reason, scholars are moving to talking about JE rather than J and E. Like E, it is difficult to identify a continuous J narrative running through the whole of the Torah.

Further, despite being the only source which can be readily identified running through the whole Torah, it seems that P is not really an independent source, but was intentionally composed so as to fit into the narrative material of J and E. Narrative disconnects between Genesis and Exodus make a continuous source running from Genesis to Numbers unlikely. For example, only a few verses (Genesis 50.14, 24; Exodus 1.8-7) superficially account for the transition from Joseph as the second most powerful person in Egypt to being unknown by the pharaoh, and the Israelites as nomads in Canaan to slaves in Egypt. Also, only a single passage in Genesis (15.13-16) gives any indication that the Israelites will have to leave Canaan first, and then return to the promised land.

In light of these issues, among European scholars there is a general move away from the traditional understanding of the Documentary Hypothesis, to understanding Genesis and the Moses story (Exodus and following) to be two competing origin narratives which were later edited together by the P source. They still see J and E (or JE) in Genesis, but do not think that J or E are complete sources running through the whole of the Torah. P is still seen as the final redactor and D is still responsible for the Deuteronomistic History.

EZRA AND NEHEMIAH

Crash Course in Jewish history

If not for legendary efforts of Ezra and Nehemiah the fledgling Jewish community in Israel would not have survived as we know it.

If history is people, the history of the Second Commonwealth begins with one of history’s greatest personalities: Ezra the Scribe, who was descended from the priestly family of Aaron. The Talmud says that if the Torah would not have been given through Moses it would have been given through Ezra (Sanhedrin 21b).

He arrived just in nick of time. The fledgling Jewish community in the Land of Israel was under siege and disintegrating. They were physically threatened. They were intermarrying. They were desecrating the Sabbath. They were assimilating. It sounds like headlines in this week’s newspaper, but it describes the situation 2,500 years ago at a major crossroads in Jewish history.

By the force of his great personality, Ezra was able reverse the terrible situation in a very short period of time.

SURVEYING THE SCENE

Ezra did not come with the original group of returnees who accompanied Zerubbabel when the decree by Cyrus was first announced that the Jews could return to their land and build their Temple (Ezra 1:1-3). As the primary disciple of Baruch the son of Neriah (who had been the primary disciple of Jeremiah), he remained by the side of his great teacher in Babylon until his passing, the Talmud says (Megillah 16b).

While in Babylon, Ezra organized a little over 40,000 Jews to return with him to the Land of Israel. Out of a population of perhaps a half million Jews that number was not very impressive. Worse, he could not conscript the caliber of Jews he wanted. The greatest Torah scholars and the Levites stayed behind.

When Ezra did arrive in the Land of Israel, he saw a Jewish community that had broken down spiritually. Some traditional sources that suggest the intermarriage rate was as high as 85-90%. The situation was so bad that the High Priest — whom all the Jewish people looked to for spiritual leadership — had sons who married non-Jewish women.

Ezra also saw that all the Jewish-owned stores in Jerusalem were open on the Sabbath, which was the market day. The non-Jews from the neighboring towns and villages would come into Jerusalem on the Sabbath to make purchases. The Jewish shop-owners told Ezra that they had found legal loopholes in Jewish law for doing so.

It was like Moses coming down from Mount Sinai with the Tablets of the Ten Commandments in his hand and seeing the Golden Calf.

Ezra also had to deal with the political problem. They were not allowed to build the Temple and the Samaritans dominated the scene – threatening with violence anyone who would oppose them.

Nehemiah Enter the second man to turn the situation around:

He was a prominent Jew who rose to very high office under the Persian emperor Darius. Hearing about the situation, he approached the king with a very brazen proposition. He asked to be allowed to take a leave of absence to help his brethren get settled and build the Temple. Then he would return.

In the ancient world, if the king did not like an idea like that you were a head shorter. It smacked of dual loyalties. Why should his most trusted advisor be worried about Jerusalem when he was working for him in the palace? Nehemiah took a great risk asking it.

Fortunately, the king agreed. Not only that, but he gave him an army contingent and carte blanche to use them as he saw fit.

When Ezra came the Samaritans were not too nervous. Another rabbi, they thought. However, when Nehemiah came he came with the might of the Persian army behind him. He came equipped to do battle. And battle he did — physical battle and political battle.

BUILDING THE WALL

Reconstruction Although decades earlier the walls of Jerusalem had been breached by the Babylonians, in effect making the city indefensible, many parts of the wall still stood. Tactically, Nehemiah realized that the first task was to fill in the gaps and create one continuous wall (Nehemiah 2:17). He organized the work right away. Quickly, the downtrodden Jews joined together and completed the wall halfway, injecting them with a new sense of hope and courage (Nehemiah 3:38).

Their enemies at first looked on mockingly and doubted their ability to build any type of useful wall. However, as it actually began to spring up before their eyes their arrogance turned into panic and they schemed to disrupt the work (Nehemiah 4:1-5).

However, Nehemiah organized them into family units capable of defending themselves at the same time they continued the work of fixing the wall. Day after day, from dawn into the night, they worked: “We labored in the work… from the break of dawn till the stars appeared” (Nehemiah 4:15).

All their work paid off and, miraculously, they completed the job in a mere 52 days. Remember, this was without heavy equipment and under the constant threat of attack. It was truly a remarkable feat.

Thanks to Nehemiah, Jerusalem now had a physical wall to protect the Jewish people. Next it was up to Ezra to set up a spiritual wall.

Ezra’s Decrees In order to be successful on any front the Jewish people had to be strengthened internally. One of the first measures took Ezra was to make an ultimatum forcing all Jewish men to divorce their non-Jewish wives or at least have the women convert. Whoever refused would be excluded from the community. For the matter of spiritual survival no compromises could be made.

Then he addressed the Sabbath desecration. The Jewish shop-owners had in many cases found legal loopholes to conduct their work on the Day of Rest. Ezra passed decrees closing the loopholes and forbidding work on the Sabbath.

Ultimately, Ezra and Nehemiah called a convention and administered what became known as, “The Covenant of Faith” (Nehemiah, Chapter 10). The people read from the Book of Deuteronomy, which describes all the laws and ideals they were not living up to. They all wept and repented, and agreed to uphold the Torah from then on, especially to observe the Sabbath, bring the tithes and donations to the Temple and refrain from intermarriage.

The Pocket Within a short five year span, Ezra and Nehemiah together turned the situation around. Nevertheless, life for the start-up Jewish community remained precarious.

The Persian Empire was massive. It stretched from India in the east to the Sahara Desert (modern day Libya) in the west. In the north it reached to the Black Sea and the Greek Islands. It encompassed four continents: Asia Minor, the Middle East, parts of Africa and Southern Europe.

By contrast, the area controlled by the Jewish people at the time of Ezra and Nehemiah was not more than a 25 mile radius from Jerusalem. The rest of the country was occupied by the belligerent Samaritans, Phoenicians, Idumeans and other fierce peoples. In short, the Jews who resettled the land in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah lived in a small indefensible enclave around Jerusalem with no natural resources surrounded by enemies and in the shadow of an ambivalent giant that trusted and distrusted them, that granted them legitimacy but did not want them to become too legitimate, that embraced them but kept them at arm’s length.

THE SECOND TEMPLE

Ezra set about building the Second Temple, but lacked the funds to give it the physical magnificence of its predecessor. On the day it was dedicated those who remembered the First Temple wept (Ezra 3:12), because it was such a far cry from its predecessor. The First Temple was made of gold and other precious metals. Its stones were magnificent marble. The wooden parts were made from cedar and acacia, the strongest and best type of wood. It was one of the wonders of the ancient world.

The Second Temple, by comparison, was small and made entirely out of wood. They could not afford to make it out of stone. It was put together quickly. It was primitive. Consequently, those who saw it and remembered what the first one was like wept. They saw in one stark comparison how far they had fallen.

The Second Temple would be rebuilt no less than four times, but it would not be until the time of Herod several centuries later that it would regain its stature as one of the wonders of the world. On one hand, Ezra’s Temple was a source of consolation. On the other hand, it was a reminder to the people how far they had fallen and how far they had to go.

NO MORE PROPHECY

The Second Temple lacked spiritual magnificence as well. It was missing, for instance, the great golden menorah-candelabra that Moses had made. It had no Ark and no Tablets of the Ten Commandments.

Furthermore, there was no more prophecy in the Second Temple era, the Talmud says (Sotah 48b). We have to realize that for a people who were accustomed to prophecy it was a wrenching experience. Prophets not only predicted the future but interpreted current events… authoritatively.

In the Second Temple era there was also a retrenchment of the Divine Providence. God worked no longer through open miracles, but through natural means. It was as if He had withdrawn or hidden His Presence.

No matter how one looked at it the Second Temple era was physically and spiritually impoverished. That was the climate in the beginning of the story of the Second Commonwealth. That is why, as we will see, the turbulence and upheavals of the next few centuries are unmatched in the annals of Jewish history. Much of it is directly linked to the nearly impossible conditions under which the Second Commonwealth began. It will be an era of almost never-ending revolution, war and internal strife.

If the Jewish people could survive the Second Temple era they could survive anything.

EZRA AND THE COMPILATION OF THE PENTATEUCH - EPISODE 63

The University of Texas, Austin February 4, 2015,

Christopher Rose, Outreach Director, Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Guest: Richard Bautch, Associate Professor of Humanities, St Edward’s University, Austin

See also Episode 67: How Jews Translate the Bible and Why University of Texas 29.4.2015

The authorship of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament–known as the Torah or the Pentateuch–has been traditionally attributed to Moses. This raised some questions, however: would the most humble of men really describe himself as such? During the Enlightenment, scholars identified four distinct authors of the Pentatuch, creating the long-standing “Documentary Hypothesis.” In the past twenty five years, a new trend in Biblical Studies has begun to challenge this long held view.

Guest Richard Bautch from St Edward’s University in Austin is one of the scholars taking a new look at the Biblical figure Ezra and his relationship to this critical text. In this episode, we discuss current thinking about the formation of the Pentateuch during the time of Ezra.

Your current work revises what is known as the “Documentary Hypothesis,” which concerns how the Pentateuch was written. Can you explain what the Documentary Hypothesis is, and some of the issues that scholars have identified with it?

Certainly, and let me provide some background first. Going back into Antiquity, actually, we as scholars can see the importance given to the figure of Moses as those first five books of the Bible were finally edited, consolidated as a collection of five books, the identity of Moses was part and parcel of that collection when it was created. Subsequently, in different religious traditions, the idea of Mosaic authorship of the entire Pentateuch was extended, really across generations. And, for scholars and laypeople alike, the idea of Moses having written all of the Pentateuch was fairly widespread, although initially readers were able to see flaws in this idea. There were points at which, for example, Moses said, “Moses is the most humble of men,” yet how could he have written that if he really was the most humble of men?

As a result, scholars were, for a period of time, sort of wondering about Mosaic authorship. Finally, with the enlightenment, scholarship in Europe especially developed an alternative way of understanding the authorship of the Pentateuch in terms of these distinct sources. Scholars, especially in Germany, designated four distinct sources in Israelite history who contributed major parts of the first five books of the Bible. These are designated by letters: You have the J source, the E source, the D source, and the P source.

Now, what’s the issue with the four source theory? It had incredible longevity, it really came to the fore in the 19th century, it really held sway for most of the 20th century as well – what is the issue with it?

Well, I see this way: essentially it became a situation where the model–i.e., the four sources–were driving the research, and so what we could have is scholars–eminent scholars–who were working with this model, but always in terms of sources. Sometimes they would posit the existence of additional sources to deal with new data–the great Otto Eisfeldt, a German scholar of the early 20th century, created an L source, for example. So, we had almost a proliferation of sources. So the model was driving the research rather than the data driving the research. And that, ultimately proved to be a real difficulty.

I have an analogy. Imagine, if you will, in molecular biology, if Watson and Crick when they came out with their great discovery–the double helix, DNA. What if what they had published was the quadruple helix? What if they had identified four strands that contained every bit of important information having to do with DNA and molecular biology? And subsequently, for a couple of decades at least, scholars all worked with this idea of four strands? But, eventually, what would happen through scientific method if nothing else, is people would look and say, “the model just doesn’t support that. When we look carefully at the data again and again and again, there’s actually only two strands. We’ve only got a double helix here, and that other material, the other data, we’ll continue to study it, work on it, and try and discover its relationship to those two strands.”

Essentially, the same thing is happening in Biblical Studies, especially in the past twenty five years, scholars–with the exception of a few–have gone from a four source theory to something rather scaled down. And at this point two of the original sources, the P source–meaning the Priestly source, and the D source, meaning the Deuteronomist, primarily found in Deuteronomy, although elsewhere–those two sources remain. Those two sources now really command our attention. So, what we are really looking at is a lot of work done on P and D and, subsequently, the other parts of the Pentateuch that are not P or D, we are looking at ways of understanding their relationship to P and D. I would just add that, for my own research and that of several others, a critical point is that, in the fourth century, BCE, that appears to be the point where these two separate sources, the priestly source on the one hand and the D source on the other, were by redactors or editors conjoined and brought together. So, at that point we have a critical stage for what is the formation of what we now know as the Pentateuch, or the first five books of the Bible.

Since you mentioned that historic period, is there are reason why then these sources would have been combined? What was going that these redactors or editors saw a need to combine these into one sources?

Well, it was a very stimulating time. It was a time when if we think in terms of Ancient Israel, the sovereign nation ended in 587 BCE with the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem. Many of the people were taken into exile, although they did return by the end of the 6th century, it was under Persian hegemony, and so we have a kind of nascent Jewish society in Jerusalem as well as a very lively diaspora at this point, representing Judaism, that’s sort of our window on Judaism. Think about the diaspora in Babylon, for example, also in Egypt, at Elephantine we have copies of significant Jewish texts as well relating to festivals and feasts and other issues that are really Pentatuechal issues.

What many believe is happening is that there is a need to create a single document or a single story which embraced both the group that was–you can say–at the center, in Jerusalem and maybe has a certain claim at least to the legacies of Ancient Israel, but also the groups in the diaspora–the diaspora in Babylon, the diaspora in Egypt as well. And if we read through those first five books, it is really curious to see how much of the action, although it is about Moses bringing the people into the promised land, how much of the action takes place outside, in other lands–adjacent lands. Abraham comes from Harran, up in modern day Syria; Moses is actually from Egypt, is he not? So, there’s a way in which the diaspora is being integrated into the story in a way that tells The Story. It’s a story of origins, really, but in a way that’s inclusive so that these different communities of Judaism, even beyond the land of Israel, have a voice and have a place in there.

Your current work involves the person of Ezra, who is the Biblical Prophet. What is his relationship to this process–this, I presume, is your hypothesis on the formation of the Pentateuch?

Great question. For a long time in earlier scholarship, the thinking was that the Pentatuech, or the Torah, was actually all put together–consolidated, edited, really for a final time–in the period of the Babylonian exile in the 6th century, so it’s a much earlier date than we’re now proposing. The thinking was that Ezra, as a historical figure, he is born in Babylon, but he returns–I shouldn’t say returns, but he brings a group of returnees to Jerusalem and, among other things, he commands an entire assembly where he reads from the Torah of Moses. That sort of indication has led many scholars to see Ezra as a seminal figure in the first proclamation of the Pentateuch, that Ezra was the first and best window on more or less the complete Torah. And all this happening in the 6th and 5th century — again, much earlier than I propose.

The way that I kind of address is in a talk I’m giving is that, they have in Biblical scholarship the concept of the primo genitor, he’s the first son, and as the first son, he is the heir, and what he will inherit is a double portion, it’s the very best of what the family has. Unfortunately, for the other sons their inheritance is virtually nothing. So, the thinking was that it’s almost as if the Torah in exile was this great Biblical figure itself, and Ezra was the primo genitor. He was the first one to inherit the best, the most pristine of the revalations of God, and he proclaimed them in Jerusalem.

So, here’s how I now understand Ezra. First of all, Ezra likely made his mission in the 4th century. The dating of Ezra has always been a little up for grabs, I think more and more scholars are now seeing him as a fourth century figure. The other thing is that the materials that we have about Ezra, if we look at them carefully–that’s kind of a separate question unto itself–but if we look at them carefully, we’ll see that they really do kind of reflect the Torah itself. Some of the things that Ezra says line up quite well with passages in the Torah, in the book of Leviticus, for example. My theory is that these two works were actually synchronous, that we should think of the formation of the Torah, and specifically the conjoining of the P and D sources, in the fourth century as happening more or less right along side the Ezra narrative as it’s being written and completed in the fourth century, in Jerusalem. So, again, my analogy is that Ezra was thought of as the Primo Genitor, but, actually, Ezra and the Pentateuch are more like close siblings. They’re more like twins if you will, who are both created from much of the same material–the D and the P material that forms and informs the Pentateuch is also very prominent in the Ezra materials. My approach now is to understand Ezra in that manner, and to use Ezra as a window on the formation of the Pentateuch.

Could we then propose that Ezra was the one who consolidated the texts, or is that either not important or not part of the story?

I think there are actually some differences when we start looking at some passages. There are enough differences, and critical differences, too, in ways of thinking and ideas that I would certainly have to bring other parties into the picture and paint a more complex picture of Priestly and Deuteronistic editors working on the Pentateuch. Ezra, increasingly, has his own contribution to make which matches up with the Pentateuch but is probably distinct from the mission, if you will, of the redaction of the Pentateuch. I would keep those separate, to be honest.

Toward wrapping up, what does this sort of revised timeline and revised understanding about the way that the Pentatuech was assembled, how does this impact our understanding of what has come to be known as the Hebrew Bible, or the Old Testament for Christians? What new interpretations can we have out of how this text was assembled?

If we think of the Second Temple period as an arc–the full arc of the Second Temple period–obviously for Christians and many Jews, the end of this time is very, very important–this is a time which receives much study, there are many texts from this period, which are intensely studied by both Christian scholars, Jewish scholars as well. What I have found is that to really understand Second Temple Judaism, and let’s say for Christians to understand the background of the Jesus story–it’s not simply the century before Jesus, as was long the approach in scholarship, with the understanding that before that we just don’t know that much–we don’t know much about the Persian period. We don’t know much about the first couple of centuries of the second temple.

That is changing radically, because we now have copious data on that, and we’re coming up with some good understandings and interpretations of that data. For me, the impact is that we now have a much broader base of background for studying the origins of Christianity, as well as Judaism late in the Second Temple period. In my own work, I continually find myself working at the beginning of the Persian period, identifying an interesting theme or topic such as penitential prayer or covenant, and then tracing the trajectory or development of one of those topics or themes all the way through the later Jewish materials and the Christian texts as well. And what I find is that there is potentially a much richer understanding for those studying the later texts if their background is not simply the decades or century before the time of Jesus in the 1st century, but if we can go all the way to the return from exile and have a really good grasp of that data. It’s there, it’s always been there, it’s canonical, but the study of it has really taken off in the last twenty five years or so, and I think that’s made all the difference.

ORAL LAW

BibliaHebraica

\

Rabbinical Judaism believes that the Torah was transmitted side by side with an oral tradition. Other groups, such as Karaite Judaism, the ancient Saducees, and Christianity do not accept this claim. Indeed, many terms and definitions used in the written law are undefined within the Torah itself; and the reader is assumed to be familiar with the context and details. This fact is presented as evidence to the antiquity of the oral tradition. An opposing argument is that only a small portion of the vast rabbinic works on the oral tradition can be described as mere clarifications and context. These rabbinic works, collectively known as "the oral law" [תורה שבעל פה], include the Mishnah, the Tosefta, the two Talmuds (Babylonian and Jerusalem), and the early Midrash compilations.

Torah SheBaal Peh (the Oral Tradition) is oral because ultimately it has no repository other than the minds of the Jewish people. Even when it was written down in the form of the Talmud, it was written is such a way that it retains a component which can only be learned from a teacher. The Oral Law is the way in which we connect with the Torah. It is the bringing of the Torah into this world all the way down until it rests in and connects with our minds. Without the Oral Law, the Torah would always be something separate from ourselves, as is the Written Torah. This would render the Torah something abstract and removed. But this was not G-d’s Will. G-d’s whole reason for creating the Torah was so that we could keep it – so that we could become walking Sifrei Torah. The Oral Law is therefore not a luxury. It is G-d’s way of ensuring the implementation of His plan

List of Hebrew Bible Events Wikipedia

The Torah. What is it? Why is it so important to the Jewish people? (Powerpoint Presentation)

Who wrote the Torah?

Tanakh

Ezra and Nehemiah

God a Brief History by John Bowker, Dorling Kindersley 2003

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

|

The Bible |

SUMMARY

________________________________

The Hebrew Bible is also called Hebrew Scriptures, Old Testament, or Tanakh (a word combining the first letter from the names of each of the three main divisions). It contains the sacred books of the Jewish people and forms a large portion of the Christian Bible. It tells of God’s dealing with the Jews as his chosen people, who collectively called themselves Israel. The first six books tell the history and genealogy of the people of Israel. The following seven books continue their story in the Promised Land, The last eleven books contain poetry, theology and additional history.

It is organized into three main sections: the Torah, or “Teaching,” Pentateuch, from the Greek for ‘five books’ or the “Five Books of Moses” which tells the story from the creation to the death of Moses.; the Neviʾim, or Prophets; and the Ketuvim, or Writings.

Many Christians refer to the Hebrew Bible as the Old Testament to distinguish it from the New Testament, which recounts the ministry and gospel of Jesus and presents the history of the early Christian church. The Hebrew Bible as adopted by Christianity features more than 24 books

The assumption that Moses was the author of the Torah began to be challenged in the 16th century. In the 19th century the Documentary Hypothesis was proposed stating that the Torah has four main sources J (Yahwist), E (Elohist), D (Deuteronomistic), and P (Priestly). Today it is thought there are two systems P and D within which J and E work.

Rabbinical Judaism believes that the Torah was transmitted side by side with an oral tradition known as the Oral Law

Choosing texts for the Bible is referred to as canonization, a method of measuring a text’s importance. The conclusion of the last section of the Bible, ketuvim (Writings) is debated; however, a majority of scholars believe its final canonization occurred in the second century CE

|

Overview Torah |

THE HEBREW BIBLE/ THE PENTATEUCH /

OLD TESTAMENT/

HEBREW SCRIPTURES/TORAH/TANAKH

|

CLICK BUTTON TO GO TO SECTION |